Fukushima Daiichi, the 10mcSv/h Zone

This Visual Narrative was originally published in French in December 2014. This English version is posted with the original publishing date, December 11th, 2014.

We reached Fukushima under light snow. Almost the cliché of a nuclear winter. The snow was not to stay long in the city, neither were we.

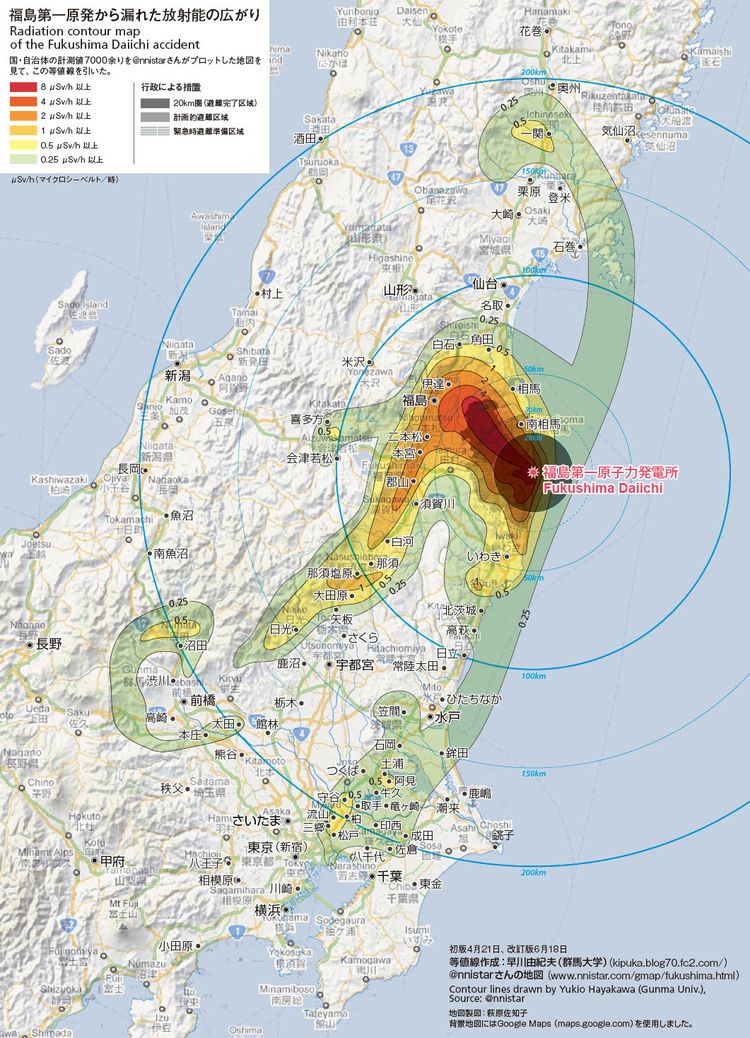

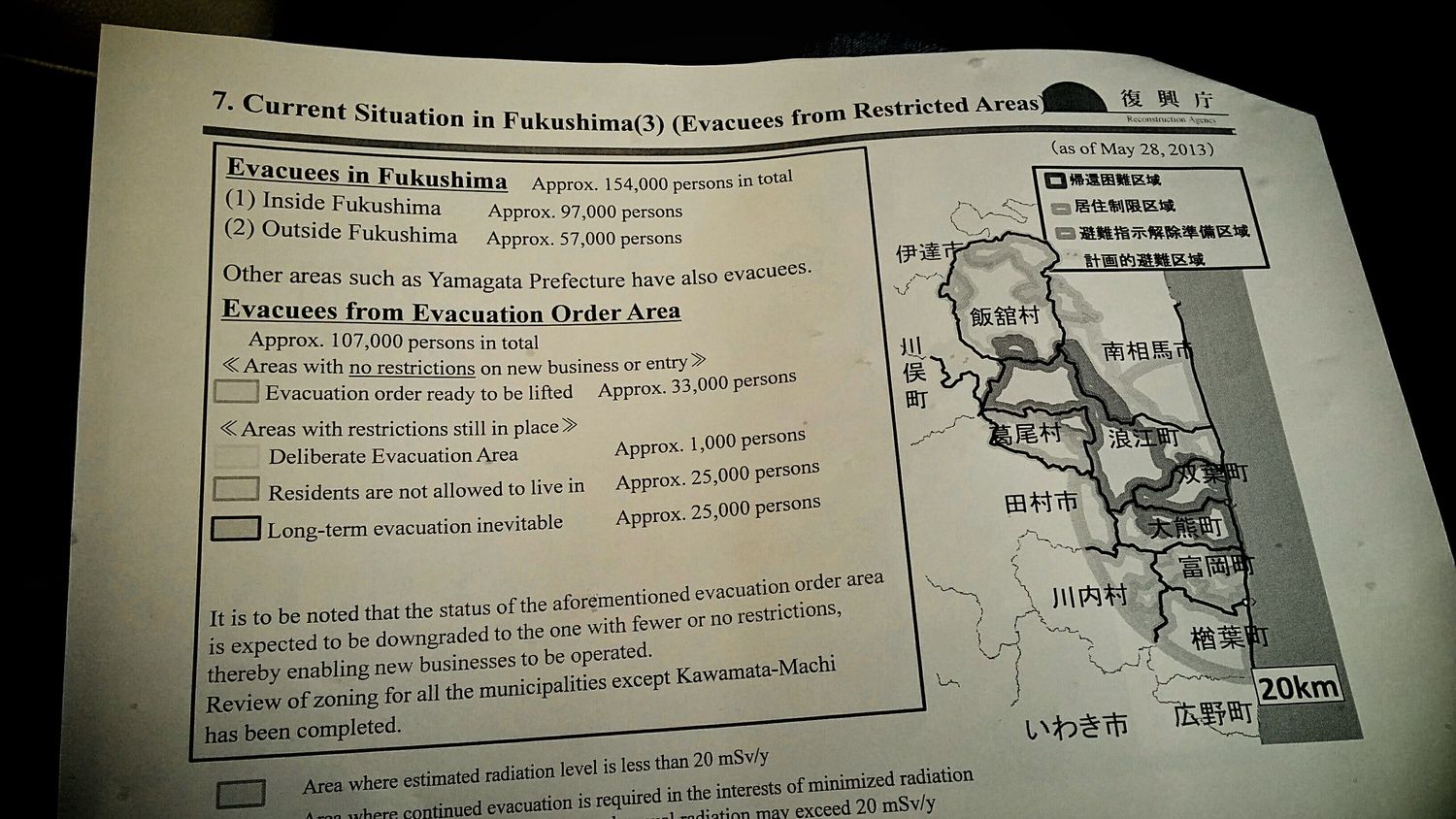

Professor K. from Fukushima University was waiting for us at the station ticket office, a surprisingly cheerful and decorated station. Professor K. immediately hands us a photocopy: the map of evacuated areas and restricted areas. “We're going there”.

We rush into the car in the colors of Fukushima University. It will allow us to enter restricted access areas.

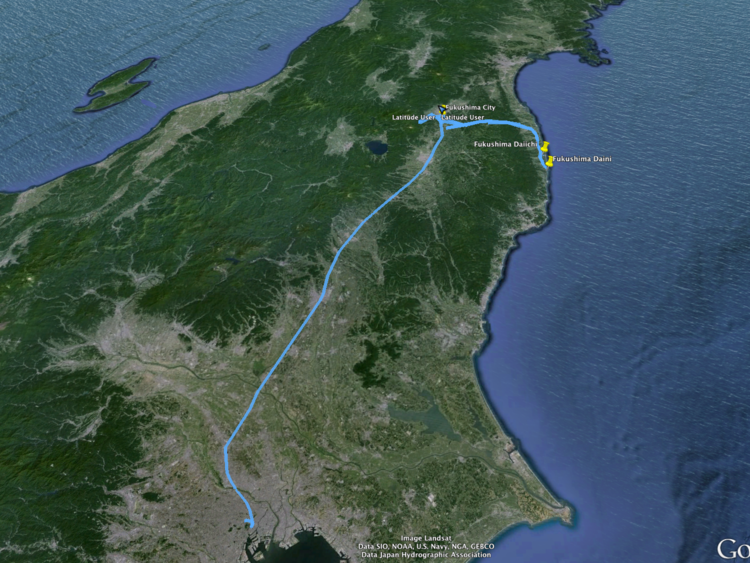

We head to Fukushima Daiichi, the nuclear power plant damaged by the tsunami on March 11, 2011.

Our aim, if possible, is to understand the current situation in the region.

We pass some neighborhoods of Fukushima City: “we can't take measurements here, inhabitants are fed up with us”. However, we stop discreetly between 2 bars of social housing. Professor K. brought a professional geiger with him. I compare the measurements with my little Russian SOEKS geiger. Substantially the same figures on both equipments.

We take the direction of Iitate. “One of the most beautiful villages in Japan”. It was before the disaster. The population has disappeared, evacuated elsewhere in the region. Since then it's been a "ghost town" as many others we've been through a lot during the day.

We meet a citizen militia made up of old people. These militias roam deserted villages to avoid looters, wild animals and the installation of criminals, the 3 current scourges of the region. How long, on a nuclear scale, can these old people protect their country?

The number of looters is in decline partly thanks to the militias and perhaps because of the Yakuza. “The Yakuza are everywhere in the region now”. They come from Kansai and Kyushu. Indeed, in a supermarket in Minamisamo, we will hear about Osaka-ben, the Osaka way to speak Japanese.

The Yakuza were brought in by the decontamination companies. They flourish in the region. They offer their services “by force”: to pass the roofs to the 'Karcher' and remove the top ten centimeters of soil from gardens. This is the decontamination racket.

As for wild animals, they abound. Wild boars, stray dogs, pigs, monkeys. We only saw monkeys this time around, by the side of the road, less than a yard from the cars. They are no longer afraid of humans who do not get out of their vehicles. You have to stay at a great distance, ...as with the Yakuza.

In Iitate we discover the mountains of contaminated earth in their black bag. Everywhere. Homeowners have to keep their nuclear waste for 30 years, on their property, in plastic bags, that won't last 10 years. I'm not sure I understood the decision chaos that led to this decision.

We take some measures. They oscillate between 1 and 2 mcSv/h at the roadside, near the bags of contaminated soil. For the geiger it is a "High Radiation" environment. Decontamination does not seem to have any effect because the measures are the same everywhere.

At the town hall of Iitate, the municipal Geiger counter has taken place next to cute handcrafted sculptures. One can imagine the tourists who came from Tokyo to the Iitate before 2011.

The region is splendid. The snow that felt during the night gently melts under the pale sun. The trees have resplendent hues. In the farms, traditional Japanese architectures. It is one of the most beautiful areas I have visited in Japan.

We set off again. Direction Minamisoma, one of the cities most affected by the tsunami.

Radioactivity is relatively low in Minamisoma. We are in the green and only 3 times more than in Tokyo, which remains our benchmark with its 0.100 mcSv/h.

There is the “Minamisoma Marathon” this Sunday. You wouldn't expect to do a marathon here. The city is cheerful and fresh. They sell and buy beautiful vegetables from the region. We weren't expecting that either.

We move away from the center to get closer to the ocean.

The cleaning job was very efficient. With the exception of a few destroyed buildings, large empty “fields”. Old rice fields, old farms. 18th century Japan must have looked like this.

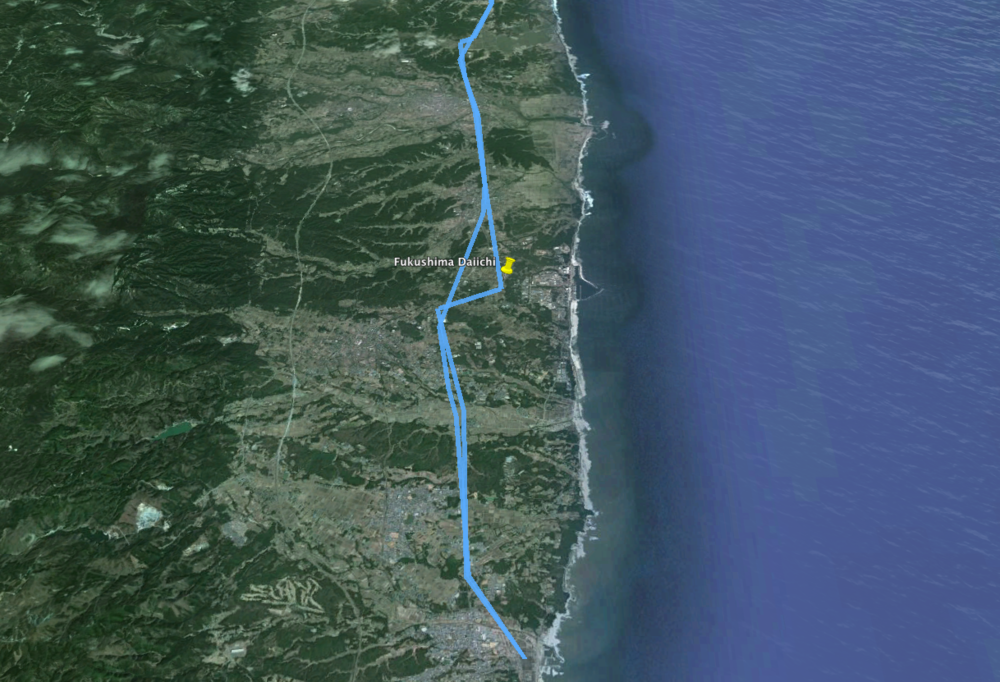

We head south towards the nuclear plant. Route 6 has reopened a few days ago.

It becomes forbidden to stop on the side of the road. At the entrances to the “kebi”, private guards block the entrances to the villages. Warnings indicate keeping a steady fast pace.

The radioactivity becomes impressive. We measure up to 9 mcSv/h. The geiger howls and indicates in red a dangerous environment. The geiger's manual says to withdraw from a red zone without waiting. In the context it is out of question and just impossible. Professor K. talks about the “new normal of Fukushima”.

Impossible not to think about if we had a road accident, whether we hit a stray animal or just get a flat tire.

Of course, Route 6 is busy. Lots of power plant workers, trucks, firefighters and police.

Everyone drives very, very fast and our Subaru is no exception, at 140km/h on a road designed for a 80km/h speed limit.

I expected to see the army, but the police are there. “She is there to help, they are very nice” we are reassured. They are also volunteers from Osaka or the rest of Japan. The suicide rate is extremely high in the ranks of the police in the region, we are told. Police's gestures invite us to drive faster.

We pass the village of Futaba. The forbidden zone. There, shops, patchinkos and restaurants remained as they were on March 11. The products are still in the showwindow, when those have not collapsed.

We arrive at the entrance to the power plant, where we can see chimneys and cranes that are busy.

The power station is a private site. No photos, no Geiger measurement, no GPS. Total blackout!

On leaving the plant, we continue our descent to Fukushima DaiNi, Daiichi's sister plant. It was also a victim of the tsunami, but her cooling system was restarted on time.

The region aligns 4 power plants on the coast. 3 were damaged by the tsunami.

Fukushima has seen decades of nuclear euphoria. Villages fought over the installation of new power plants. As the leading energy region in Japan, it found itself in the dark after March 11. Fukushima station still displays a faded “Power City”.

Corruption continues in the region. Evacuated families receive ¥ 500,000 ($5'000) per month in compensation for staying in the region. They lose these benefits if one of the parents find a job. So the parents stay home, out of work, and the pachinkos bloom again, thanks to the Yakusa. The corruption loop has come full circle.

If many solar installations have sprung up in polluted rice fields, giving a certain image of modernity, the region's problems are serious and unprecedented.

People fear the stigma, so common in the Japanese culture. Young girls fear that they will not be able to marry because of their genetically tainted origin. Many families with children have moved elsewhere in Japan. Discreetly.

Professor K., who returns to Tokyo at the weekend by car, tells us how his Tokyo neighbors, seeing his car registered in Fukushima, politely but firmly asked him to park elsewhere.

I dare to ask the difficult question: “why do people stay?” The answer is no less direct: “there are two categories of people: the fools, and the others who cannot afford to go elsewhere ”.

The point is that, with the geiger set in silent mode, after a few minutes, you already start to think that everything is back to normal. “We have arrived at the stage where we can joke about the situation between residents of Fukushima”. I have difficulty believing it.

At the end of 2014, Fukushima's economy was unstable and supported by state subsidies, now owner of TEPCO.

Tokyo wants at all costs to prevent the region from becoming an abandoned no-man's land where a new type of banditry would flourish. A temporal, financial, social puzzle when you look at the situation on the nuclear scale.

For us, it is the return to the University of Fukushima for a debriefing within the new FURE department (Fukushima Future Center for Regional Revitalization). The experience has been strong. We hope that something "new" and positive will emerge from this drama. This "new" is for us to contribute by sharing and that was the goal of this first "mission".